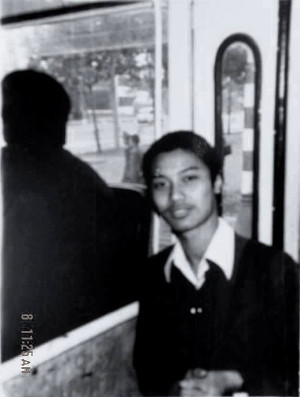

Male, 20, mechanic at the Beijing Jiaohua [Coking] Factory. From: Beijing.

At 7 a.m. on June 4, 1989, Wang was at the main entrance of the Jiaohua Factory, just having finished his night shift, when a brigade of army trucks drove by. As he was waiting to cross the street, holding the breakfast he had just bought, one of the army trucks drove into the crowd, injuring many. Wang was struck, sustaining severe injury to his internal organs. He was one of three people who died instantly at the scene, and was taken to the Chuiyangliu Hospital. His ashes are buried at the Jinshan Cemetery in the western suburbs of Beijing.

Wang was known to have been very social and outgoing. After his death, many co-workers went to visit his parents to express their condolences and to make donations.

Wang’s mother, Qi Zhiying (齐志英), is a member of the Tiananmen Mothers.

Whenever I think about my son’s death, I feel bad. Because we the parents had always been honest [and didn’t get involved in things], we didn’t expect any trouble.

I said, “Child, in the past you always left early for the night shift. Why haven’t you left for work yet today?” He said, “I was waiting for you to come back. Didn’t you say you were going out to buy groceries? I was waiting for you to come before I left.”

At that time, when my husband knew about our son’s death, he was immobilized. My husband gathered my brothers and sisters around me before they told me, because they were afraid I wouldn’t be able to take it and that they couldn’t handle my reaction. After my son was gone, whenever I saw other people’s children of my son’s age, I cried the whole day. I am always thinking that I shouldn’t have let him go to work. I was stupid; I didn’t understand what was going on. I thought: We are all down-to-earth people [and no trouble will come to us]. Why did I urge him to go to work? I have regretted it for a long time. There have been times, more than once or twice, when I saw someone and I chased after him for a few steps. Once, I saw a child very much like my oldest son and I chased him down. When I saw that it was not him, I burst into tears.

It was I who urged him to go to work, thinking that during peace time, nothing bad would happen. My child also wasn’t the type to beat, smash, or loot. And he wasn’t even going in the direction [of trouble]; he knew his place. I knew my child; there was nothing bad in him. How would I have known when I asked him to go to work that the next morning when he was buying youtiao (fried bread sticks) . . . . Many people said he was still holding a youtiao in his hand. When I think about it, I feel awful. After working the night shift, the second day, before he even had his breakfast, he died. It makes me feel so bad. Whenever I think about it, after all these years, it makes me feel terrible.

Video testimony of Qi Zhiying, mother of Wang Gang, 2009 (in Chinese)