May 15, 2019

Thirty years ago, on June 3-4, 1989, the Chinese government unleashed massive military force against civilians in Beijing, both participants and observers of an exuberant and peaceful large-scale protest centered in Tiananmen Square which had also spread to other cities. Initiated by students, the protest to call for democratic reform and an end to government corruption had been joined by teachers, intellectuals, journalists, workers, and other civilians over its 50-day course.

In one bloody night and on the days that followed, martial law troops, obeying orders from higher authorities, fired with submachine guns and pistols, crushed with tanks, and stabbed with bayonets—and brutally killed an untold number of unarmed civilians. In the June Fourth crackdown, or Tiananmen Massacre, the Chinese government’s use of the people’s army—the People’s Liberation Army—to kill its own people, in peacetime, shattered hundreds or thousands—perhaps even ten thousand or more—of Chinese families, and shocked not just the entire country but also the whole world.

Yet for 30 years, the Chinese government has not taken responsibility for its crimes against its people. Instead, it has engaged in a sustained campaign to rub June Fourth out of Chinese history, in efforts to force those who saw and suffered it to forget, and the younger people to never learn about it. The government’s attempt to erase June Fourth from history has gone hand-in-hand with its adoption of the June Fourth crackdown as a model for dealing with perceived threats to the power of the ruling Communist Party of China: absolute intolerance of critical diverse views and complete disregard for human dignity and basic rights. In that sense, the lawless violence of June Fourth—and the government impunity—exists very much in the present, and has been intensified under Xi Jinping.

This sense of impunity has been in full display, over and over, for all the world to see: the imprisonment and tragic death-in-custody of Liu Xiaobo, the reform advocate and Nobel Peace laureate; the destruction of an entire rank of rights defense lawyers and activists by imprisonment and physical and psychological torture; the outright kidnapping of foreign nationals, even on foreign soil; the silencing of intellectuals; the continued suppression of the culture and religion of the Tibetan people; and the internment of more than one million ethnic Muslims in Xinjiang in a campaign to erase their culture and religion.

“The international community’s self-interested acceptance of the Chinese leaders’ post-June Fourth ‘bargain’—economic reform, but no political reforms—and failure to hold the Chinese leadership accountable for the murder of its own people, have also sadly contributed to the ongoing trampling on rights in China today, ” said Sharon Hom, Executive Director of Human Rights in China.

“In exchange for trade benefits and entry into China’s vast labor and consumer markets, governments and foreign companies conveniently believed that China’s increased integration into the international community would help it democratize and play by international rules. Instead, in amassing enormous economic and political clout, China is changing those rules and aggressively promoting its own models of human rights, development, and democracy that are at odds with universal values,” said Hom.

International engagement with China, in particular marginalizing human rights for the sake of trade interests, has emboldened a party-state increasingly brazen about its subjugation of the rule of law under the rule by the CPC, its aim of technologically-enhanced comprehensive control over the speech and conduct of every citizen, and its ongoing violations of internationally enshrined fundamental rights.

Beyond its borders, the Chinese government is also stepping up efforts not only to rewrite international human rights principles and norms—born of the lessons the world learned from the horrors of the Second World War—but also to militarize, flout trade decisions made by international authorities that it does not like, and appropriate technology in the service of surveillance and control over cyberspace.

“The Chinese party-state has learned the lesson of 1989: that it can get away with murder. So now it is accelerating efforts to legalize repression and upgrade its surveillance and social control capabilities to equip a powerful digital authoritarianism,” said Hom.

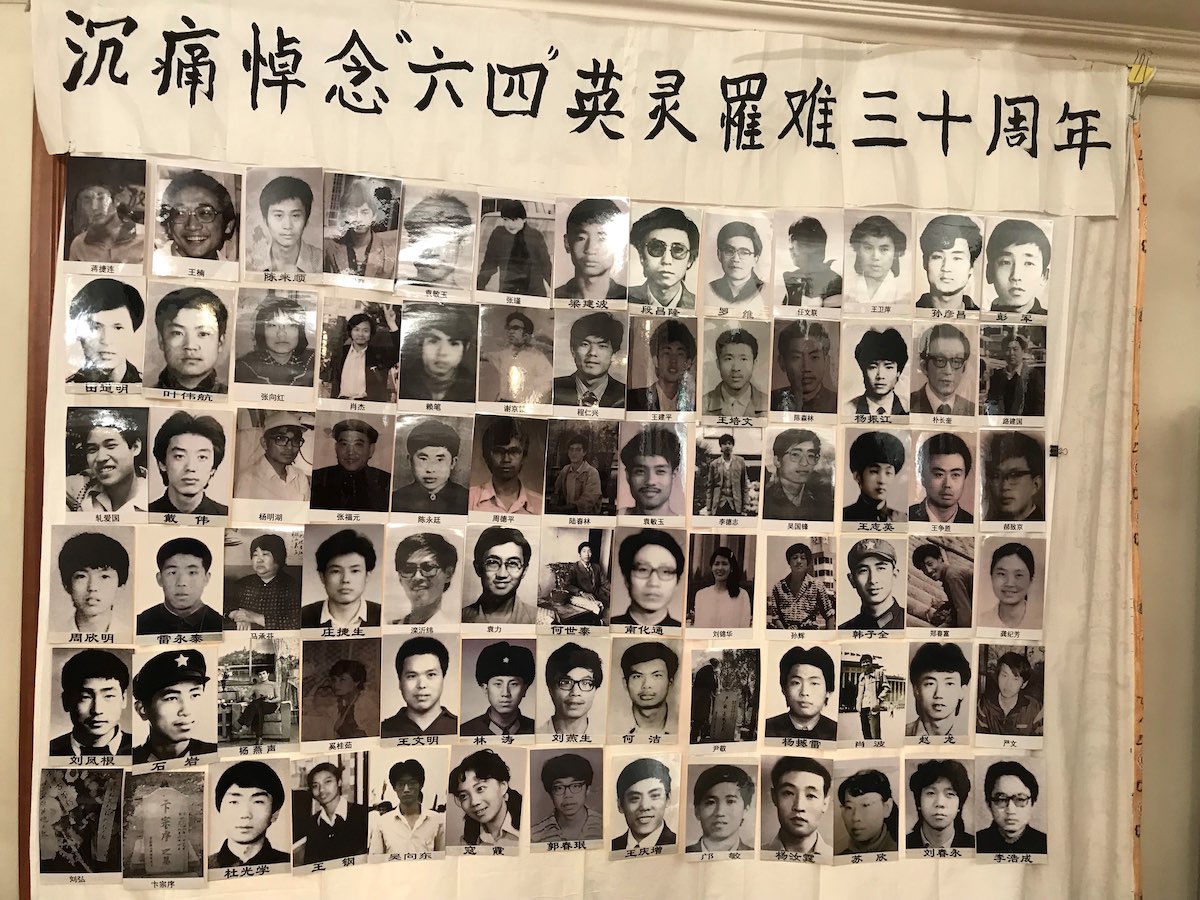

Against this formidable background, one group in China has fought against state-enforced amnesia surrounding June Fourth and has shone a steady light of evidence against ongoing government impunity, defying harassment, surveillance, and threats of retaliation: the Tiananmen Mothers. For nearly three decades, these family members of June Fourth victims along with survivors have collectively identified and documented 202 individuals killed in the June Fourth crackdown and accumulated evidence of the crimes committed against them. They have accomplished this by force of their moral outrage, mutual support, and tenacity in their pursuit of justice for their loved ones. Comprising 127 living members and 55 deceased members, the Tiananmen Mothers have never stopped pressing the Chinese authorities to respond to their three basic demands regarding June Fourth: truth, accountability, and compensation. In the steadfastness of their quest and the unwavering insistence of justice, the Tiananmen Mothers are a beacon and the conscience of Chinese civil society.

It is their work that has made possible Human Rights in China’s “Unforgotten” project: a series of profiles of June Fourth victims that draw on the documentation the group has collected and compiled. The profiles, consisting of text, photos, and videos, tell the stories of the individuals, about not only how they died, but also, wherever possible, how they lived, and how their families have been affected by their deaths.

“The dead cannot come alive again, but HRIC’s ‘Unforgotten’ project seeks to honor each life. We hope the profiles will remind the world that they were living human beings—many of them passionate and patriotic students yearning for a free and just society—whose lives were brutally crushed by a government which would go on to deny their deaths,” said Hom.

With “Unforgotten,” HRIC supports the Tiananmen Mothers’ demand for truth, accountability, and compensation for the June Fourth crackdown, and urges the international community to join in their call. The 30th anniversary of June Fourth is not only an occasion for remembrance. It is a time for truth and justice.

Members of the Tiananmen Mothers at the 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019

That the world can know about the stories of 202 victims of the June Fourth crackdown is a testament to the extraordinary achievements of the Tiananmen Mothers. Through their mission, they have unearthed information that Chinese authorities cannot look away from, accumulated evidence to support the demand for government responsibility for the cold-blooded killing, and persisted in reminding the world that the Chinese government has yet to tell the truth of what happened.

The group began as two mothers devastated by the death of their children. Ding Zilin, an associate professor of Renmin University of China who lost her 17-year-old son, Jiang Jielian, during June Fourth, described their beginning:

On June 3, 1989, at 11:00 p.m. my son Jiang Jielian was killed at Muxidi. He was a high school student, and just turned 17. On June 4, 1989, at 3:30 a,m., Wang Nan, another high school student, was killed at the southern intersection of Nanchang Road, on the west side of Tiananmen Square. He was just 19.

In September, I finally reached Wang Nan’s parents by phone.

A few days later, a middle-aged woman came to my home, accompanied by her husband. . . . She seemed calm, but you could tell she was suppressing immense pain deep in her heart. She was Wang Nan's mother, Zhang Xianling. She told me that her son's body had been dug out from a pit near Tiananmen Square; it had already started to decompose and was filled with maggots.

She was the first June Fourth victim’s family member I befriended. We decided to search for other victims' families and from that time forward, our idea began to grow.

The following year, on the day after Qing Ming (Grave Sweeping Day), Zhang Xianling sent me a note which she had found at Wang Nan's grave at the Wan'an Public Cemetery's Hall of Remains (万安公墓骨灰堂). The note said: "We share the same fate. On June 4, I lost my husband. Now my son and I rely on each other for survival. There is so much I can't come to grips with. If you wish, please contact me." In the note, the woman provided her first and last names, her address and her phone number at work. She was the second June Fourth survivor that I befriended.

The process of identifying victims and tracking families has been arduous. Names of victims were whispered to early members of the group, or delivered in slips of paper, some by university staff members, and sometimes the people who provided names and addresses of families did not even dare to identify themselves. There were times when they managed to identify the victims but could not find their parents. And even when the group managed to track down families of victims, it could take two or three years before the families felt secure enough to agree to establish contact and speak with the group.

While some families live in Beijing, many others are in other provinces, some in the remote farming hinterland, beyond where roads end. Some parents could not read or write, scratching out a living from farming. A heartbreaking fact quickly emerged: a victim from a poor family was almost always the most promising among the children—the only one child that the family could afford to send to university, whose death dashed the prospect of a better economic future for the family.

Through their search, the Tiananmen Mothers have built an extensive documentation archive on the killing and those killed, in interviews with family members (including video interviews), and in what they call “records,” essays written by members after their visits to families.

Video interview with Sun Hui’s parents: “Tiananmen Mothers Speak Out: The Story of Sun Hui (孙辉)

Video interview with Wu Guo Feng’s parents: “Tiananmen Mothers Speak Out: The Story of Wu Guofeng (吴国锋)”

Since 1995, the Tiananmen Mothers have made sustained efforts to demand justice by writing open letters to government leaders, seeking dialogue to negotiate a settlement. But the authorities have never once responded. The group now numbers 127. Fifty-five other members have passed away. In 2012, one of the members, a father, took his own life—nearly 23 years after his son’s death. He said in his suicide note that he wanted to use his own death to protest the lack of redress for the injustice done to his son. The advancing age of the members and their declining number make the group’s quest ever more urgent as each year wears on.

Because of their mission to unearth the truth, individual by individual, family by family, members of the Tiananmen Mothers have been harassed and detained. They have been put under surveillance around “sensitive” periods each year, in the lead up to the annual Two Congresses in March and, especially, to the anniversary of June Fourth. They have been deprived of their right to mourn in public. Many of those killed were gunned down in the street, but members of the group have been forbidden by the authorities to commemorate their loved ones at the locations of their killing. And at Qing Ming, Grave Sweeping Day in Chinese tradition, plainclothes policemen are deployed to follow and watch family members as they pay respects at the graves of June Fourth victims. This year, members have been told that they “will be traveled out of town” and not be allowed to speak with reporters. In March this year, many of the group gathered in a private ceremony to remember their loved ones and repeat their vow to not give up seeking justice for them.

Members of the Tiananmen Mothers holding portraits and names of their loved one, at the 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019, Yin Min (尹敏), a member of the group, reads from the essay issued by the group in March 2019, “Mourning Our Families and Compatriots Killed in the June Fourth Massacre: A Letter to China’s Leaders”

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019, Yin Min (尹敏), a member of the group, reads from the essay issued by the group in March 2019: “Mourning Our Families and Compatriots Killed in the June Fourth Massacre: A Letter to China’s Leaders”

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019, Yin Min (尹敏), a member of the group, reads from the essay issued by the group in March 2019, “Mourning Our Families and Compatriots Killed in the June Fourth Massacre: A Letter to China’s Leaders”

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019, Yin Min (尹敏), a member of the group, reads from the essay issued by the group in March 2019, “Mourning Our Families and Compatriots Killed in the June Fourth Massacre: A Letter to China’s Leaders”

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019, Yin Min (尹敏), a member of the group, reads from the essay issued by the group in March 2019, “Mourning Our Families and Compatriots Killed in the June Fourth Massacre: A Letter to China’s Leaders”

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019, Yin Min (尹敏), a member of the group, reads from the essay issued by the group in March 2019, “Mourning Our Families and Compatriots Killed in the June Fourth Massacre: A Letter to China’s Leaders”

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019, Liu Xiucheng (刘秀臣), mother of victim Dai Wei (戴伟): “Rest in peace. We will persist to the end.”

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019, Yin Min (尹敏), a member of the group, representing fellow member Ding Zilin (丁子霖), mother of victim Jiang Jielian (蒋捷连) , who cannot be present: “Dear child, on behalf of your mother, I toast you. We will be strong and persist in our path. Rest in peace.”

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019, Di Mengqi (狄孟奇), mother of victim Wang Hongqi (王鸿启): “Our children, This is a toast for you. This year marks the 30th anniversary of June Fourth. Let the whole world watch us, give us peace. Children, bless you. We will preserve. We strive to get an explanation for you. Children, please don’t worry.”

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019, Di Mengqi (狄孟奇), mother of victim Wang Hongqi (王鸿启): “My beloved children, how can your mothers endure this? How can our good children not get an explanation? Your mothers are suffering. It’s already been 30 years.”

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019, Liu Xiucheng (刘秀臣), mother of victim Dai Wei (戴伟): “The victims of June Fourth . . . . We will demand justice for you, we will persist to the end, definitely persist to the end. Rest in peace.”

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019, members of the group pay respect to the victims

At the Tiananmen Mothers’ 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019

The information compiled by the Tiananmen Mothers on the 202 victims shows that they were as young as age nine and as old as 66. One hundred and seventy-eight of them were male, 34 female. A majority—142 victims—were Beijingers, and the rest were from 21 other provinces and cities, including Inner Mongolia and Heilongjiang in the north and northeast; Sichuan, Shaanxi, and Ningxia in the west; Jiangsu, Shanghai, and Zhejiang on the eastern coast; and Fujian in the south.

They were students in an elementary school, middle schools, high schools, and universities; they were workers, drivers, engineers, chefs, a musician, demobilized soldiers, office workers, and more. They were sons of peasant families, of intellectuals, and of those who dedicated their lives to the Communist Party of China. One man was the son-in-law of the deputy chief procurator of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate. They were patriotic students; they were retirees; one was a woman en route to stay with her recently widowed mother who was home alone; and one was a student who was shot at close range by an officer when he was trying to mediate between the troops and students. Some had been helping to take the wounded to hospitals before they themselves were rushed to hospitals on flatbed carts. And there were those who were deliberately targeted because they were taking photographs of what was happening.

Six of the individuals in “Unforgotten”: (counter clockwise from upper right) Zhang Jin, Wang Nan, Su Xin, Shi Yan, Wu Guofeng, Chen Yongting

Many were killed by martial law troops firing indiscriminately into crowds; at least one person was stabbed with a bayonet after being shot multiples times; several people at the rear of a retreating procession of student protestors already far from Tiananmen Square were crushed by tanks coming from behind them; some were run over by military trucks while standing at the roadside waiting to cross the street; one person was shot in the head as he turned on the kitchen light in his eighth-floor apartment.

Many of the wounded who arrived in the hospital still breathing were met by doctors ordered to treat soldiers only; family members who went to hospitals to claim the bodies of their loved ones were told to hurry before troops came to remove evidence; and bodies were hastily buried in the front lawn a high school by soldiers—also to remove evidence. Cruelty was inflicted upon even the ashes of those killed: many families said that the cinerary halls where the ashes of their loved ones were kept refused to extend the storage period after three years—on order from the local authorities.

The profiles in “Unforgotten” are only a fraction of the 202 victims documented by the Tiananmen Mothers. And the 202 are undoubtedly only a tiny fraction of the yet-untold number of unarmed civilians deliberately and brutally killed by Chinese government troops.

As the stories told in the profiles make clear, June Fourth is about unfinished business—justice long overdue from the Chinese government.