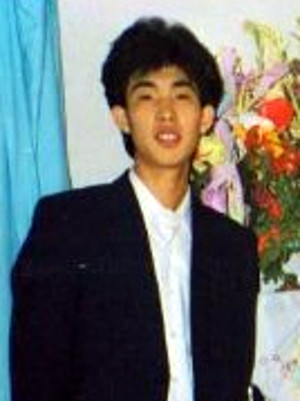

Male, 27, driver for Beijing Municipal Gas Company in the city’s southern suburbs. Lived in: Beijing.

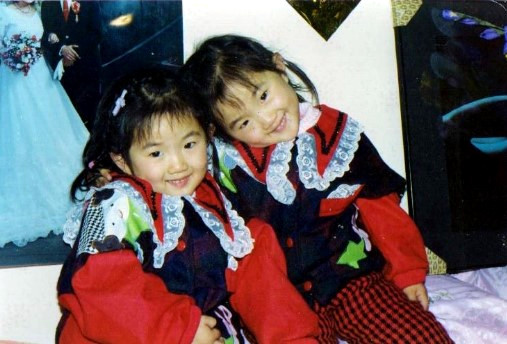

On the evening of June 3, 1989, Wang went home after finishing work, but headed out again with his wife on their bicycles. In Xidan, they became separated in the crowd, and neither returned home that night. Their families and colleagues looked for them everywhere but were not able to find them. Finally, on June 7, Wang’s family recognized him among the photos of the dead posted at the Beijing Emergency Center. They then learned that he had been hit by a bullet in the left side of his chest when he was at the intersection of Xidan Street and Chang’an Avenue. He died early in the morning of June 4 at the Beijing Emergency Center. A doctor told Wang’s family that when Wang was carried into the hospital, he was still groaning in pain, and there still seemed to be a chance to save his life if he had been treated immediately. But the orders from above were to only treat injured soldiers, not civilians. Wang’s mother said her son was an honest man who was very popular at his work unit. Wang left behind 8-month-old twin girls. His ashes are kept at the Dongsheng Cinenary Hall in Beijing’s Haidian District.

Wang Jianping’s mother, Yuan Shumin (袁淑敏), is a member of the Tiananmen Mothers.

Wang Jianping’s twin girls

Why do I say I have no more tears? I’ve cried so much that my tears have run dry. At that time whenever I sat down to eat, I would think of him. I remember one day it was pouring rain, and I sat on the street waiting for him. I couldn’t believe he was gone, and I said that one day he’d return, barefoot like when he was a child. Before he died, I didn’t have high blood pressure, but now I’ve got both high blood pressure and heart disease. Why? Well who can I talk to about what happened? I only have myself to try and hold things together. Anyway, after he died I went to the hospital and my blood pressure was very high. At its lowest it was 110, but it would go all the way up to 180. And it’s stayed that way. . . .

There are no human rights in China, but we need them. I’ve had principles ever since I was very little. You need principles to conduct yourself in society. However, if my country isn’t going to give us human rights, we will have to fight for them ourselves. After my son was killed, I’ve become more open-minded—I’ve been thinking more and I’ve understood more. Before, I only knew how to work—I didn’t understand anything. As a mother, I cannot give up. My son didn’t commit any crimes. He was innocent. For several years, in the lead up to June 4, people from my work unit and the police would come. What could I say to them? I told them I wasn’t going to say anything. I said to them, “Whatever I say to you, you can’t solve anything.” Even the police, when they came, this was what I said to them, “Is there a problem or not? If there’s no problem then just go. You say you want to talk, but there’s nothing to talk about. . . . ”

When June 4 came, I don’t know who told them I had signed something, but six people from my work unit came to find me. I said, “What are you doing here?” They replied, “Lao Yuan, we’re just here to check up on you.” I told them, “You’ve come too late. When my son was killed, not a single one of you came, not even a dog. So what’s the point of your coming to see me now?” Then they asked, “Lao Yuan, did you sign something or not?” I told them, “Yes I did. What about it?” They then asked, “Who’s your organizer?” I replied, “I don’t know of any organizer. Everyone just spontaneously organized. . . . Look, do you have any other business? If there isn’t any, please just go!” In the end, they said to me: “Lao Yuan, what happened to you?” I told them, “That’s right. I’m different now. I’m not the old Lao Yuan you knew from the factory.”