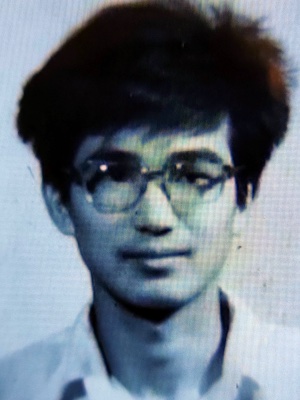

Male, 27, graduate student in the philosophy department of Renmin University of China. From: Xingziwan Village, Hengshan Town, Wujiang City (now a district in Suzhou), Jiangsu Province.

Lu was shot dead by martial law troops at Muxudi on the night of June 3, 1989. Before he died, he gave his ID to a pedestrian for him to take back to the university. His body was retrieved by the university and cremated. Lu’s ashes are buried in the mulberry garden of his home in Jiangsu.

Lu grew up in a poor family and, as a child, had to beg for food with his mother. Although his parents could not read or write, Lu and his younger brother were hardworking students and were admitted to university. To lessen the burden on his family, Lu would often spend his vacations translating book manuscripts to earn money to cover his own expenses. He was working on a manuscript when he was shot.

In 1995, when a group of family members of June Fourth victims first wrote to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress demanding a fair resolution of June Fourth, his parents felt that they must put their names on the letter, saying that not doing so would have let their son down. They also gave the group a piece of paper on which they had stamped their names a dozen times using their seals, indicating that for future signature campaigns, the group always had their permission.

Lu Chunlin’s mother, Lu Yubao (陆玉宝), and father, Lu Masheng (陆马生), were both members of the group before they passed away in 2020 and 2013, respectively.

Lu Chunlin

Lu Yubao (陆玉宝), mother of Lu Chunlin

Lu Chunlin

Lu Chunlin’s mother Lu Yubao (陆玉宝) (center), with Ding Zilin (left) and Zhang Xianling, 1996

Lu Chunlin’s parents had invited me several times to their home to meet with them. . . .

One day in late April 1995, I took advantage of the proximity of my relatives’ home in Wuxi, where I was staying, to the Lu family, and went by myself to visit them. The Lus lived in a typical village by Lake Taihu, surrounded by networks of rivers. The only linkage between the villagers and the outside world was small wooden paddle boats and motorized clay boats. But from Wuxi I was unable to go on a boat. The only option was to take the train, a long distance bus, and then a motorized three-wheeled cart (“bouncy car”) used by the peasants. The whole way I was bumping up and down, and when finally I had almost arrived at the home of the Lu family, the cart stopped beside a farm field. The owner of the cart told me that from that point forward, there was only a small foot path along the fields, not accessible for vehicles. There was still about 2-3 li (0.31 miles) left. It was almost noon before I finally found the home of the Lu family.

Lu’s mother pulled me inside the house and sat me down. At this moment I realized that she was still wearing the hand sewn old-fashioned sea blue blouse made of homespun cloth, and she had a white headscarf wrapped around her head. This was an outfit I knew as peasant’s clothing as a child, but I couldn't have imagined that half a century later, in the countryside south of the Yangtze River, you would still see this type of clothing.

That evening, the Lus had me stay in the room Lu Chunlin used before his death. Lu’s old father opened a drawer that had been sealed with dust for years to let me look through the things that Lu had left behind. I discovered that all of the books that he had read and all the things that he had used, even a piece of paper that had turned yellow, were all undamaged and kept. Among the items was a translation manuscript Lu had been unable to complete before he died. Lu’s old mother told me that to this day, she did not have the courage to go through her son’s things and photographs. She said that just looking at them would make her cry.

During that night, I stayed all by myself in the cold and empty room. My head felt completely full, and yet at the same time completely empty. It was as if a cold gust had penetrated my heart and lungs. . . .

In 1995, our group of June Fourth victims’ families wrote for the first time to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, demanding that the NPC pass law to justly resolve the June Fourth issue. I brought a first draft of the open letter with me, wishing to hear the two elders’ views. Taking into consideration their circumstances in the village, I initially did not want to collect their signatures. But after I had read the draft to them, without a word, the two elders requested that their names be included. They said that not doing so would be to let their son down.