Male, 17, student at the High School Affiliated to Renmin University of China. From: Beijing.

Jiang Jielian was an active participant in the 1989 Democracy Movement. At around 10:30 p.m. on June 3, 1989, Jiang—who had been locked inside his home by his parents, fearing danger outside—jumped out of the bathroom window and left home. Shortly after 11 p.m., as he was passing through Muxidi toward Tiananmen Square, martial law troops charged into Muxidi. Jiang was shot in front of Building No. 29 behind a long flower bed on Fuxingmenwai Street. The bullet entered the left side of his back and hit his heart. When he was brought to the Beijing Children’s Hospital, he had already stopped breathing. The hospital records read: “Dead on arrival.” Jiang was among the first group of people killed in Muxidi on the night of June 3, 1989. His ashes are kept in the shrine at his parents’ home.

Jiang Jielian is the son of Jiang Peikun (蒋培坤) and Ding Zilin (丁子霖), professor and associate professor, respectively, of Renmin University of China. Ding Zilin became a key founder and spokesperson of the Tiananmen Mothers, of which Jiang Peikun was a key member before he passed away.

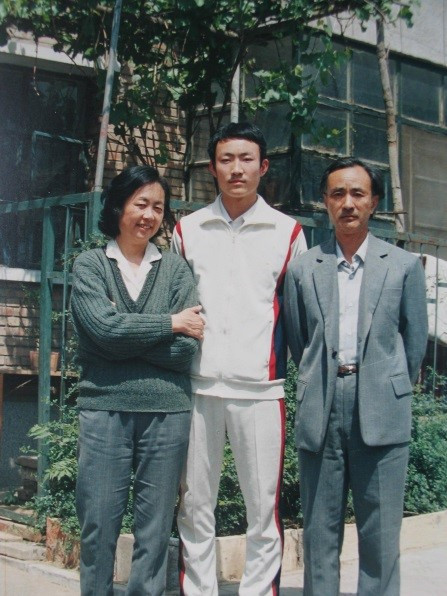

The last photo of Jiang Jielian with parents, mother Ding Zilin and father Jiang Peikun, May 1, 1989

Yin Min (尹敏), a member of the Tiananmen Mothers, holding the photo of Jiang Jielian, son of Jiang Peikun and Ding Zilin, at the group’s 30th anniversary commemoration of June Fourth victims, March 2019

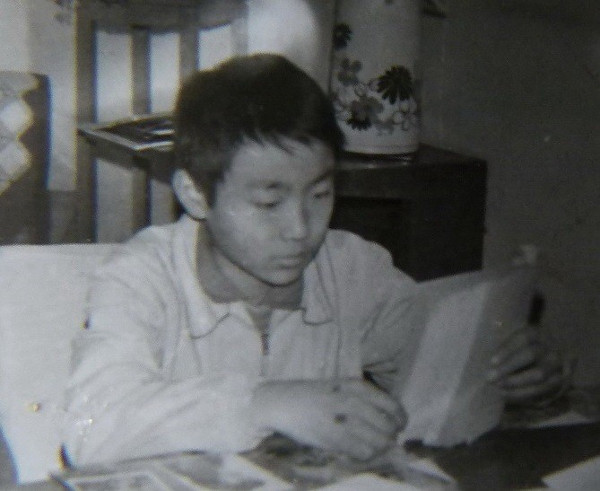

Jiang Jielian in 1986

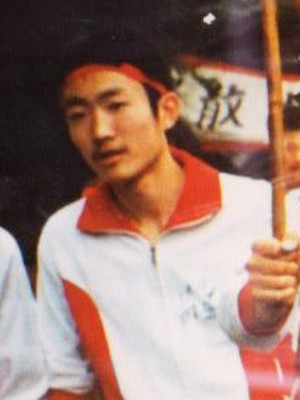

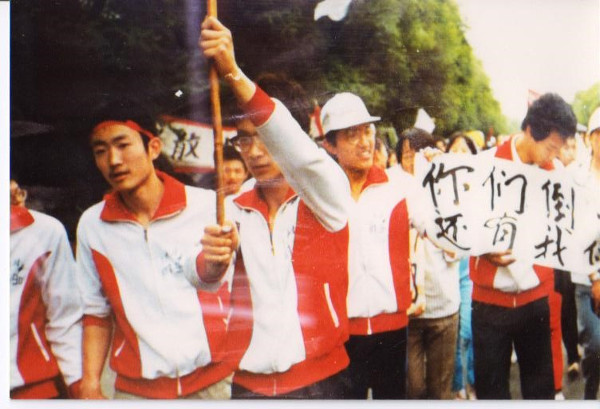

On May 17, 1989, over 1,000 students from the High School Affiliated to Renmin University marched in support of the university students on hunger strike. The banner says: “When you fall, you still have us!” Jiang Jielian, on left, is one of the march’s organizers

Jiang Jielian’s memorial service

On May 17, not only the ordinary people of Beijing but even the various democratic parties who always obeyed the Communist Party of China merged into the torrent of millions of protesters and demonstrators in the capital . . . .

We found out later that this was the first time that Beijing secondary school students went to Tiananmen Square to support the university students on hunger strike. Later we also learned from Jielian’s classmates that this march was organized by Jielian and several of his classmates. . . .

On the night of June 3, the sky was overcast, and it was muggy and oppressive. . . . Unexpectedly, the situation in Beijing suddenly changed. On television, we saw broadcast after broadcast repeat the urgent notice from the martial law troops, saying that the government was planning some sort of action, and urging citizens throughout the city to stay home, or else accept the consequences. . . . But as soon as our son heard the urgent notice, he could no longer stay put. He anxiously asked us: "What should we do? What should we do? There are still so many university students in Tiananmen Square." I told him: "Nothing. The only thing that could be done was for Beijingers to take to the streets and go to the square, but now even that can’t be done." I pleaded with him: "It's too dangerous outside, don't go out again." But he was anxious to go out, and criticized me for being a coward. . . .

I said to him: “You're just a high school student, even if you go, what can you do?” He answered with the words of an Olympic athlete: “What’s important is not what you do, but that you participate.” After saying this, he turned around toward me and kissed me lightly on the cheek, saying: "This is good-bye." . . .

It never dawned on me that we were parting forever. . . . A little after 6:00 a.m. on the morning of June 4, a young man who looked like a student came to our house accompanied by his father, and said he was Jielian's classmate. He told us that Jielian had been seriously wounded, lost a lot of blood, and had been sent to a hospital, but that he didn't know which one. He went on to tell us what had happened.

He said that at around 10:30 p.m., he'd run into Jielian at the gate of Renmin University riding a black bicycle, and that Jielian invited him to go to Tiananmen Square together. At first, the classmate didn't want to go, but he agreed in the end. Just as they were riding past the end of the Muxidi Bridge, they saw that the area was packed with people, and they could hear intermittent shouting in the distance. Meanwhile, the street at the western end of the bridge was full of armored personnel carriers and rows of martial law troops ready for action. The entire street was blocked, and vehicles and people were unable to pass. They left the bicycles on a nearby patch of grass.

He said that at this very moment, the martial law troops opened fire, with a concentration of bullets strafing the crowd of people around them. At first, they thought they were rubber bullets. But seeing the rifle flashes on the street and the crowd scattered to avoid being hit, they hid behind a flower terrace south of Building No. 29, on the north side of the north exit of the Muxidi subway station. Just then, the strafing by machine guns and automatic weapons escalated. Suddenly, a bullet struck Jielian's back, and another bullet shattered his ankle bone. The classmate said he heard Jielian saying to him casually: "I think I've been hit! Get out of here!" After saying this, Jielian staggered for a few steps, then squatted down, and passed out on the ground, his t-shirt soaked in blood. . . .

On June 4, Beijing was like a city that had gone through a violent war. The cries that had not long before reverberated throughout the night had stopped, but sporadic stray bullets could still be heard whizzing through the air around the city; the smell of gunpowder permeated the streets; there were abandoned tanks and military vehicles all over the place, and bloodstains everywhere. All of the trees, flowers, plants, and buildings on both sides of the streets seemed to be hanging their heads low, weeping for the catastrophe that the ancient city had suffered.

Shrine commemorating the 100th day after Jiang Jielian’s death